Difference between revisions of "Numerical Integration"

m (Fix image links) |

|||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | Note: the old version of this page is here: [[Old Numerical Integration]] | ||

| + | |||

Numerical integration constitutes a broad family of algorithms for calculating the numerical value of a definite integral. This the backbone of physics simulations because it allows calculation of velocity and position from forces (and therefore acceleration) applied to a rigid body. | Numerical integration constitutes a broad family of algorithms for calculating the numerical value of a definite integral. This the backbone of physics simulations because it allows calculation of velocity and position from forces (and therefore acceleration) applied to a rigid body. | ||

==Criteria== | ==Criteria== | ||

| − | In realtime simulations, the most important integrator criteria are performance, stability, and accuracy. Performance refers to how long it takes to perform the integration for a given timestep. Stability refers to how well the integrator copes with stiff constraints such as high spring constants before errors becomes unacceptably large. Accuracy refers to how well the integrator matches the expected result, | + | In realtime simulations, the most important integrator criteria are performance, stability, and accuracy. Performance refers to how long it takes to perform the integration for a given timestep. Stability refers to how well the integrator copes with stiff constraints such as high spring constants before errors becomes unacceptably large. Accuracy refers to how well the integrator matches the expected result. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Integrator Order== | ||

| + | The order of a numerical integrator is a convenient way to approximate the accuracy of an integrator. All integrators presented here have an order of at least one, which means that they eventually converge to the correct solution if the timestep is small enough. First order methods converge to the exact solution in a linear relation to the timestep. Higher order methods converge to the correct solution in a power relation to the timestep. | ||

==Euler Integration== | ==Euler Integration== | ||

| − | The Euler method is a first order numerical procedure for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a given initial value. It is the most basic | + | The Euler method is a first order numerical procedure for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a given initial value. It is the most basic explicit method for numerical integration for ordinary differential equations. |

| + | real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); | ||

| + | state.x += state.v * dt; | ||

| + | state.v += a * dt; | ||

| − | a = | + | ==SUVAT== |

| − | x += v*dt | + | The "suvat" method takes its name from the variables in the equations of motion. This is a first order method that is very similar to the Euler method. The only difference is the addition of an acceleration term to the equation for the change in position. |

| − | v += a*dt | + | real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); |

| + | state.x += state.v * dt + a*dt*dt*0.5; | ||

| + | state.v += a * dt; | ||

==Newton-Stormer-Verlet (NSV) / Symplectic Euler / Euler–Cromer algorithm== | ==Newton-Stormer-Verlet (NSV) / Symplectic Euler / Euler–Cromer algorithm== | ||

| − | + | The Euler–Cromer algorithm or symplectic Euler method or Newton-Stormer-Verlet (NSV) method is a modification of the Euler method for solving Hamilton's equations, a system of ordinary differential equations that arises in classical mechanics. It is a symplectic integrator, which is a class of geometric integrators that is especially good at simulations of systems of undamped oscillators. Due to this property, it preserves energy better than the standard Euler method and so is often used in simulations of orbital mechanics. It is a first order integrator. | |

| + | real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); | ||

| + | state.v += a * dt; | ||

| + | state.x += state.v * dt; | ||

| − | + | ==Basic Verlet/Velocity Verlet== | |

| − | v += | + | Verlet integration is a numerical integration method originally designed for calculating the trajectories of particles in molecular dynamics simulations. The velocity verlet variant directly calculates velocity. It is a second order integrator. Unfortunately, this method is unsuitable for simulations where the acceleration is dependent on velocities, such as with a damper. The modified verlet variant below uses some tricks to try to get around this limitation, but this method will only provide first-order accuracy. |

| − | + | if (!have_oldaccel) | |

| + | oldaccel = system.GetAcceleration(state); | ||

| + | |||

| + | state.x += state.v*dt + 0.5*oldaccel*dt*dt; | ||

| + | state.v += 0.5*oldaccel*dt; | ||

| + | real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); | ||

| + | state.v += 0.5*a*dt; | ||

| + | |||

| + | oldaccel = a; | ||

| + | have_oldaccel = true; | ||

| − | == | + | ==Improved Euler/Trapezoidal/Bilinear/Predictor-Corrector/Heun== |

| − | + | The so-call "Improved Euler" method, also known as the trapezoidal or bilinear or predictor/corrector or Heun Formula method, is a second order integrator. | |

| − | + | STATE predictor(state); | |

| − | + | predictor.x += state.v * dt; | |

| − | + | predictor.v += system.GetAcceleration(state) * dt; | |

| − | x += v*dt | + | STATE corrector(state); |

| − | + | corrector.x += predictor.v * dt; | |

| − | v += | + | corrector.v += system.GetAcceleration(predictor) * dt; |

| − | + | state.x = (predictor.x + corrector.x)*0.5; | |

| + | state.v = (predictor.v + corrector.v)*0.5; | ||

==Runge Kutta 4== | ==Runge Kutta 4== | ||

| − | The Runge–Kutta methods are an important family of implicit and explicit iterative methods for the approximation of solutions of ordinary differential equations. The Runge Kutta 4 (or RK4) is a well-known | + | The Runge–Kutta methods are an important family of implicit and explicit iterative methods for the approximation of solutions of ordinary differential equations. The Runge Kutta 4 (or RK4) is a well-known fourth-order explicit Runge Kutta algorithm. The code snippet shown below is high level, and the actual implementation is a bit more complicated. Note that the evaluate() function calls the system's acceleration function. |

| − | + | DERIVATIVE a = evaluate(state, 0, DERIVATIVE(), system); | |

| − | + | DERIVATIVE b = evaluate(state, dt*0.5, a, system); | |

| − | + | DERIVATIVE c = evaluate(state, dt*0.5, b, system); | |

| − | + | DERIVATIVE d = evaluate(state, dt, c, system); | |

| + | |||

| + | const float dxdt = 1.0/6.0 * (a.dx + 2.0*(b.dx + c.dx) + d.dx); | ||

| + | const float dvdt = 1.0/6.0 * (a.dv + 2.0*(b.dv + c.dv) + d.dv); | ||

| + | |||

| + | state.x = state.x + dxdt*dt; | ||

| + | state.v = state.v + dvdt*dt; | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Performance Comparison== | ||

| + | In most simulations, calculation of the system's acceleration function is computationally very expensive. Therefore, we can rank the integrators by how many times they evaluate the system's acceleration function: | ||

| + | {| cellspacing="0" border="1" | ||

| + | !Method | ||

| + | !Evaluations of the Acceleration Function | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Euler | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !SUVAT | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !NSV | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Modified Verlet | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Improved Euler | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !RK4 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because of the extra evaluations of the acceleration function, the Improved Euler method is about twice as slow as the Euler method, and the RK4 method is about four times as slow as the Euler method. Another way to look at this is that we could run the Euler method with a 0.001 second timestep with the same performance as running the RK4 method with a 0.004 second timestep. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Detailed comparison== | ||

| + | For comparing these algorithms I used a damped spring-mass system because it can be difficult to integrate when the spring is very stiff or the damping is high, but it can be analytically solved so I have something to compare the integrators to. The damping force is proportional to the velocity state, while the spring force is proportional to the position state. Zeta is the damping ratio. The analytic solution can be obtained with the following calculations: | ||

| + | real zeta = c / (2.0 * sqrt(k*m)); | ||

| + | real w = sqrt(k/m); | ||

| − | + | if (zeta < 1.0) //underdamped | |

| − | + | { | |

| − | + | real wd = w*sqrt(1.0-zeta*zeta); | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | real A = ic.x; | |

| + | real B = (1.0/wd)*(zeta*w*ic.x+ic.v); | ||

| + | real out = (A*cos(wd*time)+B*sin(wd*time))*exp(-zeta*w*time); | ||

| + | return out; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | else if (zeta > 1.0) //overdamped | ||

| + | { | ||

| + | real beta = c/m; | ||

| + | real rminus = 0.5*(-beta-sqrt(beta*beta-4.0*w*w)); | ||

| + | real rplus = 0.5*(-beta+sqrt(beta*beta-4.0*w*w)); | ||

| + | real A = ic.x - (rminus*ic.x - ic.v)/(rminus-rplus); | ||

| + | real B = (rminus*ic.x-ic.v)/(rminus-rplus); | ||

| + | real out = A*exp(rminus*time)+B*exp(rplus*time); | ||

| + | return out; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | else //critically damped | ||

| + | { | ||

| + | real A = ic.x; | ||

| + | real B = ic.v + w*ic.x; | ||

| + | |||

| + | return (A + B*time)*exp(-w*time); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | |||

| + | The spring constant (k) was fixed at 600,000. Mass was set to 168 kg. Initial conditions were X = 1 m and V = 0 m/s. The damping coefficient was calculated depending on the damping ratio (zeta). These values were chosen to be similar to what may be encountered in VDrift. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Timesteps were varied between 0.001 seconds and 0.020 seconds. To account for performance differences, the improved Euler method was handicapped with a timestep twice as large as the indicated timestep, and the RK4 method was handicapped with a timestep four times as large as the indicated timestep. The mean absolute error is plotted for each integrator at each timestep. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Critically Damped System=== | ||

| + | First, a damping ratio of 1 is simulated. Systems such as car suspensions are often critically damped. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Stability==== | ||

| + | [[File:zeta1.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Reading left to right along the timestep increments, the RK4 integrator's results become unacceptable first at a timestep of 0.009 seconds (remember that this actually means a 0.036 second timestep due to the performance handicap of the RK4 method). The NSV is next, followed by the modified verlet and improved euler methods. The suvat method is second to last to become unacceptable and the euler method is acceptable even with a 0.020 second timestep. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Accuracy==== | ||

| + | [[File:zeta1closeup.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Looking at a closeup of the results, it becomes apparent where the strengths of higher order integrators lie. At 0.002, the RK4 (actual timestep 0.008) and improved euler (actual timestep 0.004) methods beat out all of the other methods. Of the first order methods at 0.002, from most to least accurate they are: modified verlet, suvat, euler, and nsv. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From these results we can conclude that when the system is not stiff (that is, the forces involved are small relative to the timestep), higher order integrators are most accurate, even after penalizing their lower performance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Overdamped System Stability=== | ||

| + | Here a damping ratio of 2 is simulated. Systems with a lot of friction, such as tire simulations, are often overdamped systems. | ||

| − | + | [[File:zeta2.png]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In order from least to most stable: rk4, improved euler, nsv, modified verlet, suvat, euler. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Underdamped System Stability=== | |

| − | + | Here a damping ratio of 0.1 is simulated. Oscillating systems such as planetary orbits are underdamped. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:zeta0.1.png]] |

| − | + | In order from least to most stable: euler, suvat, improved euler, rk4, nsv, modified verlet. We can see why systems of orbits and molecular dynamics are often simulated with NSV or velocity verlet methods: they maintain stability very well here. | |

| − | + | ==Summary== | |

| + | Let's rank each integrator in terms of accuracy, and then stability for critically-, over-, and under-damped systems. One is the best. Recall that because we already penalized improved euler and RK4 methods for performance, we can consider each method to have roughly the same performance. | ||

| + | {| cellspacing="0" border="1" | ||

| + | !Method | ||

| + | !Accuracy | ||

| + | !Stability: critically-damped | ||

| + | !Stability: over-damped | ||

| + | !Stability: under-damped | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Euler | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |tied 1/2 | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !SUVAT | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |tied 1/2 | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !NSV | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |tied 3/4 | ||

| + | |tied 1/2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Modified Verlet | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |tied 3/4 | ||

| + | |tied 1/2 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Improved Euler | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !RK4 | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | Note that no integrator is clearly the worst or clearly the best; they all have strengths and weaknesses. If you are simulating a non-stiff system that will generate only small forces relative to your timestep, the RK4 method is the winner. If you're simulating a strictly stiff underdamped system, use the NSV or modified verlet methods. If you're simulating a strictly stiff overdamped or critically damped system, use the Euler or SUVAT methods. If you have a combination of needs, some compromise is called for. | |

| − | + | VDrift requires stability in the face of stiff overdamped systems, and currently uses the SUVAT method due to slightly improved accuracy over the euler method. | |

| − | + | [[Category:Development]] | |

Latest revision as of 07:19, 27 August 2012

Note: the old version of this page is here: Old Numerical Integration

Numerical integration constitutes a broad family of algorithms for calculating the numerical value of a definite integral. This the backbone of physics simulations because it allows calculation of velocity and position from forces (and therefore acceleration) applied to a rigid body.

Criteria

In realtime simulations, the most important integrator criteria are performance, stability, and accuracy. Performance refers to how long it takes to perform the integration for a given timestep. Stability refers to how well the integrator copes with stiff constraints such as high spring constants before errors becomes unacceptably large. Accuracy refers to how well the integrator matches the expected result.

Integrator Order

The order of a numerical integrator is a convenient way to approximate the accuracy of an integrator. All integrators presented here have an order of at least one, which means that they eventually converge to the correct solution if the timestep is small enough. First order methods converge to the exact solution in a linear relation to the timestep. Higher order methods converge to the correct solution in a power relation to the timestep.

Euler Integration

The Euler method is a first order numerical procedure for solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) with a given initial value. It is the most basic explicit method for numerical integration for ordinary differential equations.

real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); state.x += state.v * dt; state.v += a * dt;

SUVAT

The "suvat" method takes its name from the variables in the equations of motion. This is a first order method that is very similar to the Euler method. The only difference is the addition of an acceleration term to the equation for the change in position.

real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); state.x += state.v * dt + a*dt*dt*0.5; state.v += a * dt;

Newton-Stormer-Verlet (NSV) / Symplectic Euler / Euler–Cromer algorithm

The Euler–Cromer algorithm or symplectic Euler method or Newton-Stormer-Verlet (NSV) method is a modification of the Euler method for solving Hamilton's equations, a system of ordinary differential equations that arises in classical mechanics. It is a symplectic integrator, which is a class of geometric integrators that is especially good at simulations of systems of undamped oscillators. Due to this property, it preserves energy better than the standard Euler method and so is often used in simulations of orbital mechanics. It is a first order integrator.

real a = system.GetAcceleration(state); state.v += a * dt; state.x += state.v * dt;

Basic Verlet/Velocity Verlet

Verlet integration is a numerical integration method originally designed for calculating the trajectories of particles in molecular dynamics simulations. The velocity verlet variant directly calculates velocity. It is a second order integrator. Unfortunately, this method is unsuitable for simulations where the acceleration is dependent on velocities, such as with a damper. The modified verlet variant below uses some tricks to try to get around this limitation, but this method will only provide first-order accuracy.

if (!have_oldaccel)

oldaccel = system.GetAcceleration(state);

state.x += state.v*dt + 0.5*oldaccel*dt*dt;

state.v += 0.5*oldaccel*dt;

real a = system.GetAcceleration(state);

state.v += 0.5*a*dt;

oldaccel = a;

have_oldaccel = true;

Improved Euler/Trapezoidal/Bilinear/Predictor-Corrector/Heun

The so-call "Improved Euler" method, also known as the trapezoidal or bilinear or predictor/corrector or Heun Formula method, is a second order integrator.

STATE predictor(state); predictor.x += state.v * dt; predictor.v += system.GetAcceleration(state) * dt; STATE corrector(state); corrector.x += predictor.v * dt; corrector.v += system.GetAcceleration(predictor) * dt; state.x = (predictor.x + corrector.x)*0.5; state.v = (predictor.v + corrector.v)*0.5;

Runge Kutta 4

The Runge–Kutta methods are an important family of implicit and explicit iterative methods for the approximation of solutions of ordinary differential equations. The Runge Kutta 4 (or RK4) is a well-known fourth-order explicit Runge Kutta algorithm. The code snippet shown below is high level, and the actual implementation is a bit more complicated. Note that the evaluate() function calls the system's acceleration function.

DERIVATIVE a = evaluate(state, 0, DERIVATIVE(), system); DERIVATIVE b = evaluate(state, dt*0.5, a, system); DERIVATIVE c = evaluate(state, dt*0.5, b, system); DERIVATIVE d = evaluate(state, dt, c, system);

const float dxdt = 1.0/6.0 * (a.dx + 2.0*(b.dx + c.dx) + d.dx); const float dvdt = 1.0/6.0 * (a.dv + 2.0*(b.dv + c.dv) + d.dv);

state.x = state.x + dxdt*dt; state.v = state.v + dvdt*dt;

Performance Comparison

In most simulations, calculation of the system's acceleration function is computationally very expensive. Therefore, we can rank the integrators by how many times they evaluate the system's acceleration function:

| Method | Evaluations of the Acceleration Function |

|---|---|

| Euler | 1 |

| SUVAT | 1 |

| NSV | 1 |

| Modified Verlet | 1 |

| Improved Euler | 2 |

| RK4 | 4 |

Because of the extra evaluations of the acceleration function, the Improved Euler method is about twice as slow as the Euler method, and the RK4 method is about four times as slow as the Euler method. Another way to look at this is that we could run the Euler method with a 0.001 second timestep with the same performance as running the RK4 method with a 0.004 second timestep.

Detailed comparison

For comparing these algorithms I used a damped spring-mass system because it can be difficult to integrate when the spring is very stiff or the damping is high, but it can be analytically solved so I have something to compare the integrators to. The damping force is proportional to the velocity state, while the spring force is proportional to the position state. Zeta is the damping ratio. The analytic solution can be obtained with the following calculations:

real zeta = c / (2.0 * sqrt(k*m));

real w = sqrt(k/m);

if (zeta < 1.0) //underdamped

{

real wd = w*sqrt(1.0-zeta*zeta);

real A = ic.x;

real B = (1.0/wd)*(zeta*w*ic.x+ic.v);

real out = (A*cos(wd*time)+B*sin(wd*time))*exp(-zeta*w*time);

return out;

}

else if (zeta > 1.0) //overdamped

{

real beta = c/m;

real rminus = 0.5*(-beta-sqrt(beta*beta-4.0*w*w));

real rplus = 0.5*(-beta+sqrt(beta*beta-4.0*w*w));

real A = ic.x - (rminus*ic.x - ic.v)/(rminus-rplus);

real B = (rminus*ic.x-ic.v)/(rminus-rplus);

real out = A*exp(rminus*time)+B*exp(rplus*time);

return out;

}

else //critically damped

{

real A = ic.x;

real B = ic.v + w*ic.x;

return (A + B*time)*exp(-w*time);

}

The spring constant (k) was fixed at 600,000. Mass was set to 168 kg. Initial conditions were X = 1 m and V = 0 m/s. The damping coefficient was calculated depending on the damping ratio (zeta). These values were chosen to be similar to what may be encountered in VDrift.

Timesteps were varied between 0.001 seconds and 0.020 seconds. To account for performance differences, the improved Euler method was handicapped with a timestep twice as large as the indicated timestep, and the RK4 method was handicapped with a timestep four times as large as the indicated timestep. The mean absolute error is plotted for each integrator at each timestep.

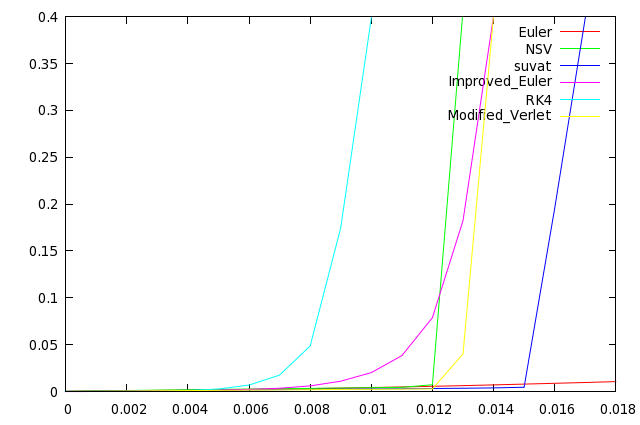

Critically Damped System

First, a damping ratio of 1 is simulated. Systems such as car suspensions are often critically damped.

Stability

Reading left to right along the timestep increments, the RK4 integrator's results become unacceptable first at a timestep of 0.009 seconds (remember that this actually means a 0.036 second timestep due to the performance handicap of the RK4 method). The NSV is next, followed by the modified verlet and improved euler methods. The suvat method is second to last to become unacceptable and the euler method is acceptable even with a 0.020 second timestep.

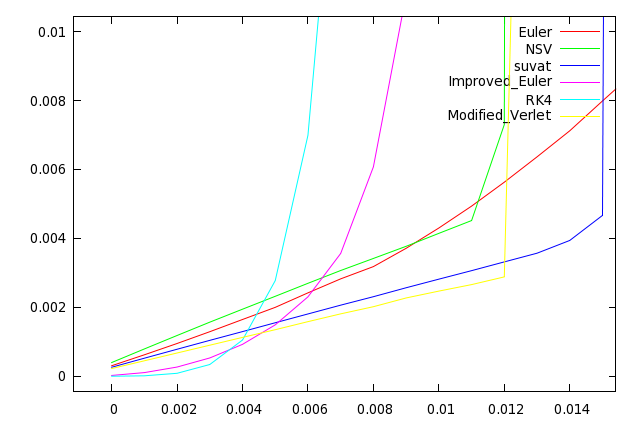

Accuracy

Looking at a closeup of the results, it becomes apparent where the strengths of higher order integrators lie. At 0.002, the RK4 (actual timestep 0.008) and improved euler (actual timestep 0.004) methods beat out all of the other methods. Of the first order methods at 0.002, from most to least accurate they are: modified verlet, suvat, euler, and nsv.

From these results we can conclude that when the system is not stiff (that is, the forces involved are small relative to the timestep), higher order integrators are most accurate, even after penalizing their lower performance.

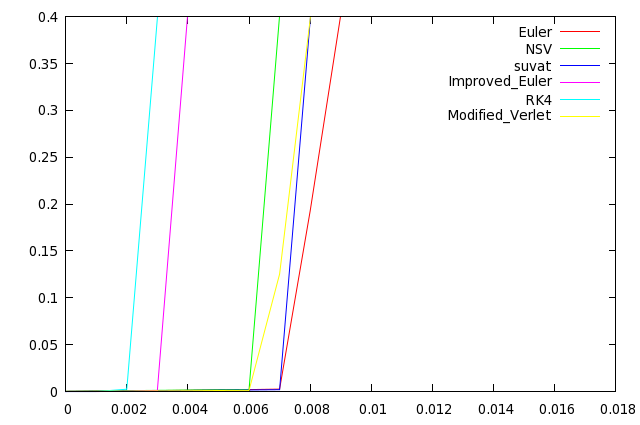

Overdamped System Stability

Here a damping ratio of 2 is simulated. Systems with a lot of friction, such as tire simulations, are often overdamped systems.

In order from least to most stable: rk4, improved euler, nsv, modified verlet, suvat, euler.

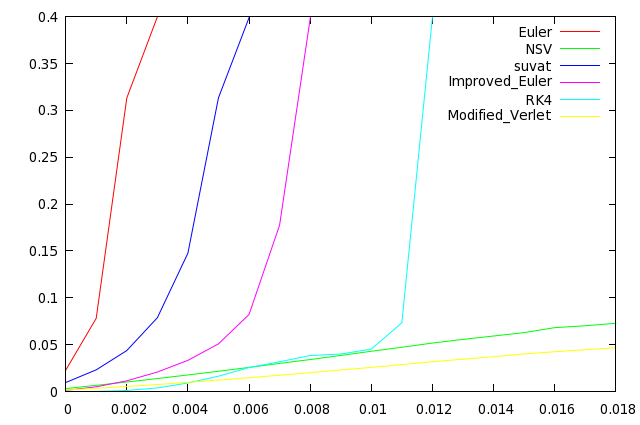

Underdamped System Stability

Here a damping ratio of 0.1 is simulated. Oscillating systems such as planetary orbits are underdamped.

In order from least to most stable: euler, suvat, improved euler, rk4, nsv, modified verlet. We can see why systems of orbits and molecular dynamics are often simulated with NSV or velocity verlet methods: they maintain stability very well here.

Summary

Let's rank each integrator in terms of accuracy, and then stability for critically-, over-, and under-damped systems. One is the best. Recall that because we already penalized improved euler and RK4 methods for performance, we can consider each method to have roughly the same performance.

| Method | Accuracy | Stability: critically-damped | Stability: over-damped | Stability: under-damped |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler | 5 | 1 | tied 1/2 | 6 |

| SUVAT | 4 | 2 | tied 1/2 | 5 |

| NSV | 6 | 4 | tied 3/4 | tied 1/2 |

| Modified Verlet | 3 | 4 | tied 3/4 | tied 1/2 |

| Improved Euler | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| RK4 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

Note that no integrator is clearly the worst or clearly the best; they all have strengths and weaknesses. If you are simulating a non-stiff system that will generate only small forces relative to your timestep, the RK4 method is the winner. If you're simulating a strictly stiff underdamped system, use the NSV or modified verlet methods. If you're simulating a strictly stiff overdamped or critically damped system, use the Euler or SUVAT methods. If you have a combination of needs, some compromise is called for.

VDrift requires stability in the face of stiff overdamped systems, and currently uses the SUVAT method due to slightly improved accuracy over the euler method.